On Body Vessel Clay and my unorthodox family of women potters

Being part of Body Vessel Clay: Black Women, Ceramics & Contemporary Art is a huge honour to me as the exhibition highlights many of the reflections I have had in the past years; elevates crafts and women; and it simple is an outstanding display of artistic excellence, sisterhood and clay politics.

How did I end up here?

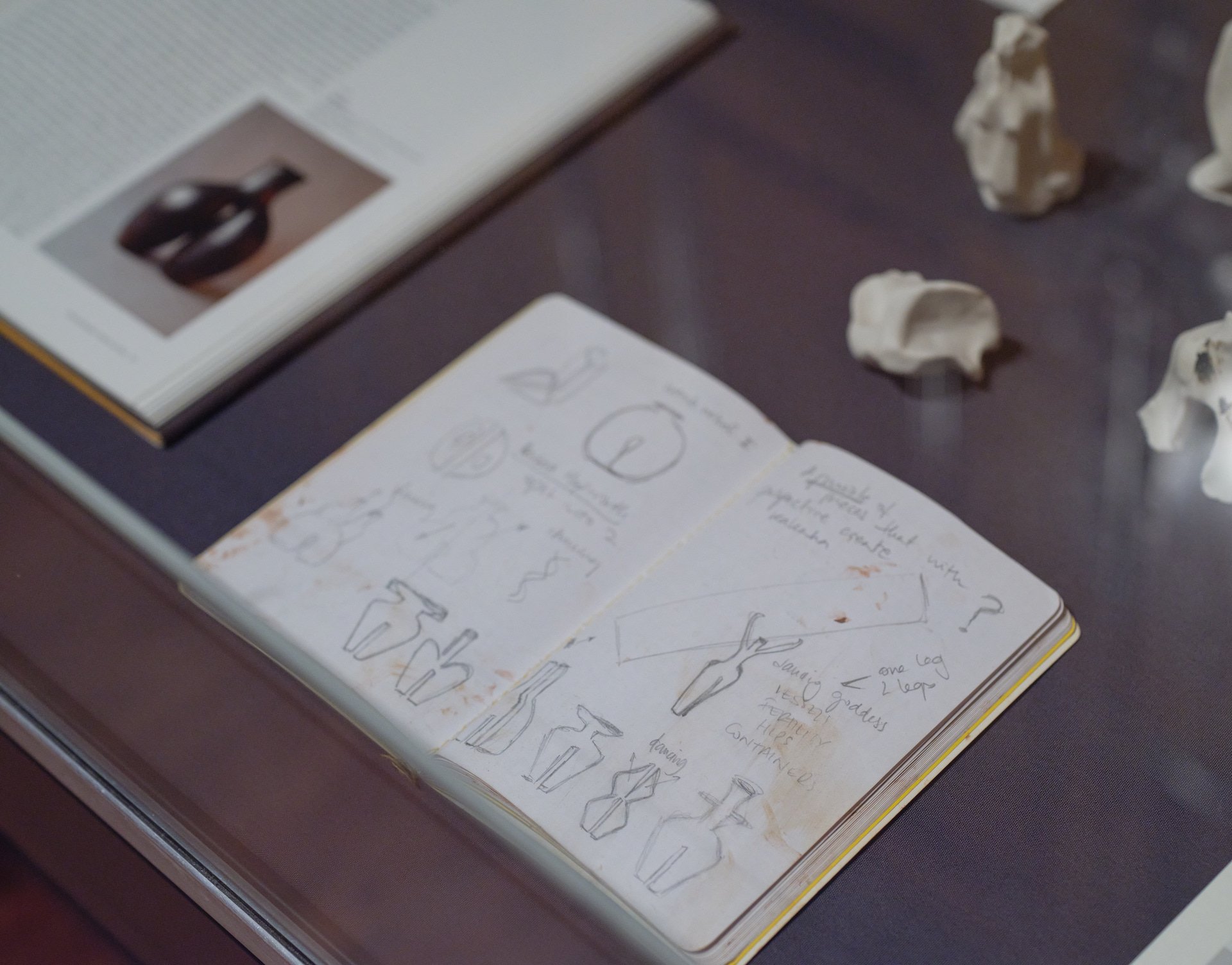

When I was looking for inspiration for my 2020 project Baney Clay: An Unearthed Identity, I wanted to make forms that evoked the pottery traditions in Equatorial Guinea (EG). Surprisingly, I couldn’t find a trace of such traditions there. Moreover, once chatting to one of my uncles in Baney, talking about my work and what I was after, he asked me ‘but what do you mean by pottery exactly?’.

I still find it hard to believe that there is no pottery tradition I can find in EG. I had always believed that clay had been part of every single civilisation, tribe or group. So what happened there? Researching remotely, miles and miles away, has proved challenging, so hopefully I will visit EG again soon to do some more digging, both literally and figuratively.

Consequently, I started looking at other traditions in the African continent. So much beauty to choose amongst. And then I saw the piece. Perfect for what I had in mind, for the goal of my project which was to reflect upon my own heritage and identity as a mix-raced woman, in between cultures and world views. And also, to challenge what it is we consider valuable in Western, post-colonialist and patriarchal societies.

Kouame Kakaha (born Tanoh Sakassou, Ivory Coast, ca. 1960), Clay Vessel, ca. 1995

Months after the project had been exhibited and had gained considerable visibility given the timely nature of the topic in the summer of 2020, I found out - while doing some more in-depth research - that there was a name behind that piece: Kouame Kakaha. A potter born in Tanoh Sakassou in Ivory Coast, ca. 1960.

The horror and disappointment at myself that I felt then followed me for a while. I felt I had betrayed her and just as the Western tendencies I tend to question, I had taken without consideration, leaving her story behind. So, I decided to try to find her.

What I find interesting about her story (the very little I know about it for now) is that while one of her pieces is at the National Museum of Natural History and/or the Museum of African Art (both Smithsonian Institution) in the US, along with a collection of Baule material, all donated by Susan Vogel; and her work was auctioned by Sotheby’s selling for 5,938 USD, there’s barely any information about her out there.

This made me think about how in Western cultures we look at and deal with objects. We often take them and use them for our own profit and discard the stories behind them. We just do not care.

What I know about Kouame is that she made the traditional pottery of her village, Baule, as she was taught. At the same time, very much like Ladi Kwali or Halima Audu, she developed her own style, which was very successful among Western buyers.

“The abstract form, the result of dreams and internal meditation, then underwent a long process of trial an error to delve it into a form that was aesthetically pleasing and able to survive the firing process.”

Jerome Vogel on Kouame’s work on Material Differences: Art and Identity in Africa by Frank Herreman

Kouame Kakaha, image courtesy of Susan Vogel

“Kouame Kakaha has continued to make forms that are markedly different from those made by other potters. She has created a number of vessels ranging from containers to ashtrays with ram decorations, although other potters prefer birds, chickens and fish.”

Jerome Vogel on Kouame’s work on Material Differences: Art and Identity in Africa by Frank Herreman

With this collection I want to celebrate her and all the other women in the Global South whose herstories our society once chose to forget. In the case of the women potters, their making domestic wares, within their homes, in groups, surrounded by children, making by hand - opposed to on the wheel - and using low-temperature earthenware clays, meant that their labour, their art, was not worthy. And when it was, like in the case of Kouame Kakaha, she was not.

At the same time, my own identity search continues. Now, more focused on my artistic identity. I am growing more and more interested in sculpture, playing with other materials, challenging my skills and finding new creative pathways.

The Searching for Kouame Kakaha pieces are my current stop in this journey. The two legs are still there, as they represent my being rooted in the past and all the women that preceded me from whom I am drawing inspiration. The tops now have come to life.

Fingerprints, eyes. The clay in movement, poking out, disappearing.

Breakages and birth. Waves of dynamism.

That interest in movement has been present in my work since my very first days making and in my main body of work until now, the Brumas pieces.

The collection also comprises two vessels that are more of a direct response to Ladi Kwali and Magdalene Odundo’s pieces, next to whom my work is exhibited. A Water Jug and a Womb Vessel through which I explored surface decoration using the qualities of different clays. Those rounded shapes are very dear to me as, to me, they represent womanhood and our power to birth life, just like clay.

I have always been jealous of and craved for the way some potters have learnt their craft: from their mothers and grandmothers; generation after generation. Thanks to Body Vessel Clay and its exploration of familial and intergenerational links among women whom we would traditionally consider unrelated women, from different countries, across countries, I have realised that I also am learning from my grandmothers and mothers. Albeit in an unorthodox way.

I thought I would never meet them. Thankfully, this show has taken me to them.

I hope Kouame Kakaha also thinks her story is in good company.

You can read more about the project and see more images here.